The Strange History of Tarot

“Beautiful cardboard face

I love you as an old friend

despite your unyielding guard

of the symbols shrouded

in the mysterious tarot pack

that beguile and defy us all”

Excerpt of “Ode” by Stuart Kaplan from The Encyclopedia of Tarot, vol 1.

Pierpont Morgan Library, Murray Hill, Manhattan. Image source: Jeffrey Zeldman via Flickr Creative Commons

Piermont Morgan Library. Image source: Tam Pollard via Flickr Creative Commons

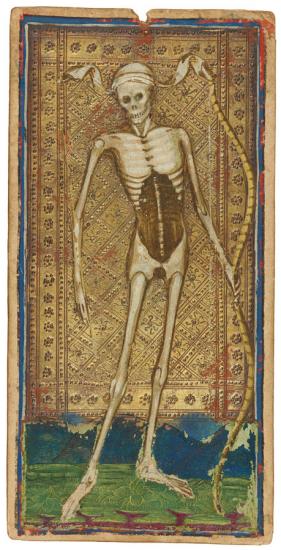

In New York City, not far from Grand Central Station, there lies an important piece of tarot history. Among its collection of illuminated manuscripts and historical documents, Morgan Library and Museum owns one of the oldest, most intact tarot decks in the world. It was commissioned 566 years ago by two members of an Italian aristocratic family. Historians refer to it as the Visconti-Sforza tarot deck, after its two commissioners: Filippo Maria Visconti and his son-in-law Francesco Sforza. The Visconti-Sforza pack represents one of the oldest known tarot decks.

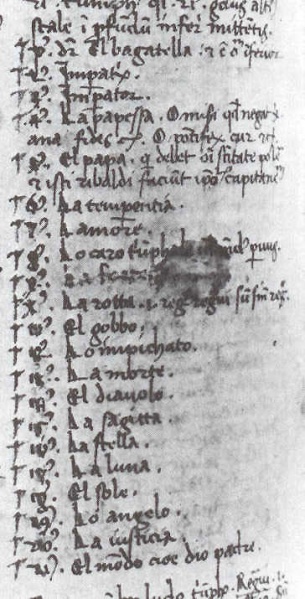

Tarot did exist prior to the creation of the Visconti-Sforza deck. Tarot, also known as tarocchi, trumphi, or Trionfi, was a popular playing card game in Italy during the 1400s. Tarocchi was popular enough during that time to be mentioned in a sermon calling for the cards to be banned. The document, known as the “Steele Sermon” or the Sermones de Ludo Cum Aliis, details a playing card deck with trump cards such as el Matto (The Fool), La Temperantia (Temperance), El Diavolo (The Devil), L’amore (Love) and other others, totaling 21 cards. These card names should sound familiar to modern tarot readers.

The Fool in the Visconti-Sforza tarot deck. Image source: Piermont Morgan Library

Sermones de Ludo cum Aliis, also known as the Steele Sermon. Image source: Tarotpedia

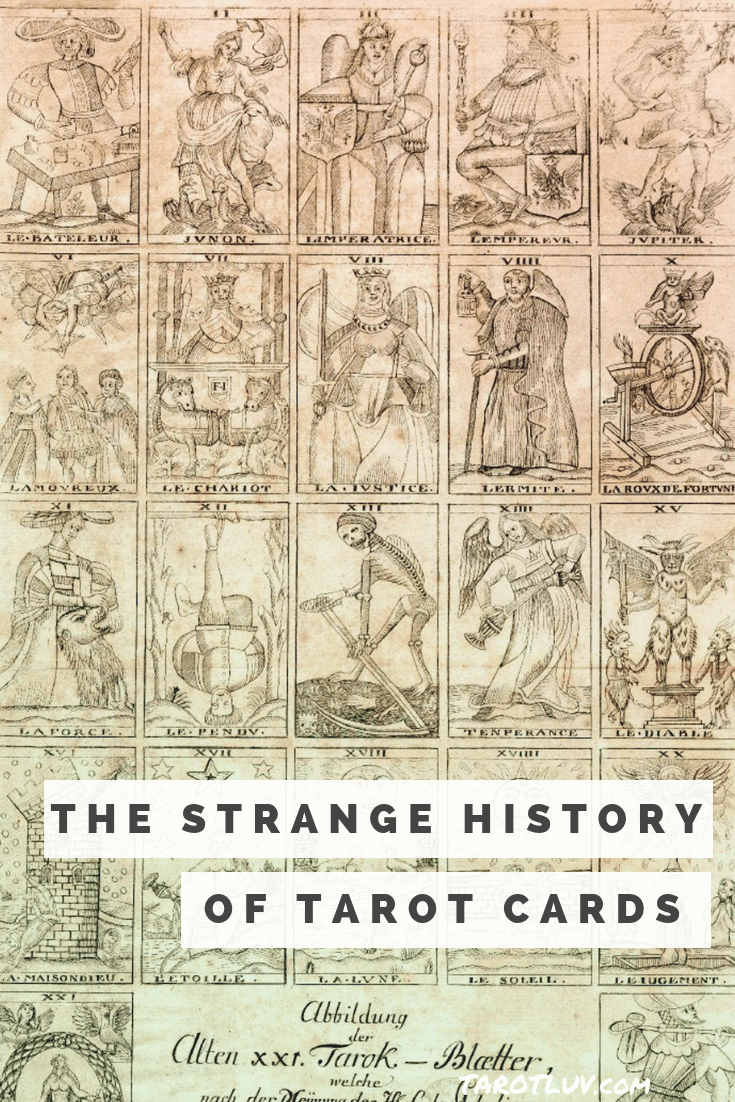

Sets of tarot cards from historical decks are housed in museums all over the world. It makes sense: the history of tarot is significant, weaving its way through material history via the invention of playing cards, art history, and printmaking. Its evolutionary timeline runs along social and philosophical revolutions through the centuries. A game that was intended for entertainment has transformed over the ages from cards for fortune-telling, to a set of mysterious keys to an esoteric truth, to a tool for spiritual transformation, to a vehicle for creativity and expression. We have dubious claims from 18th-century mystics of an Egyptian origin for tarot. Even more suspect is the folklore circulated that tarot is a relic from the Knights Templar.

How did Tarot go from an amusing card game for Italian aristocrats to a modern spiritual tool for enlightenment? The answer is a long one that weaves itself through many twists and turns.

Let’s start at the beginning.

From Here to There: The Death Card in the Visconti-Sforza Tarot to the Happy Tarot

Etymology of Tarot

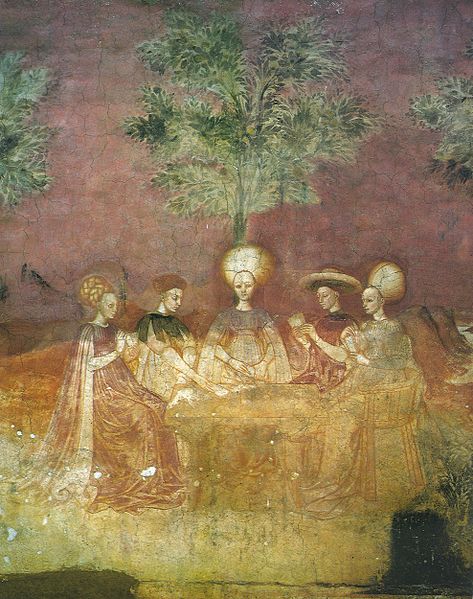

The Tarocchi Players fresco in Casa Borromeo, Milan. 1440s. Image source: Wikimedia Commons

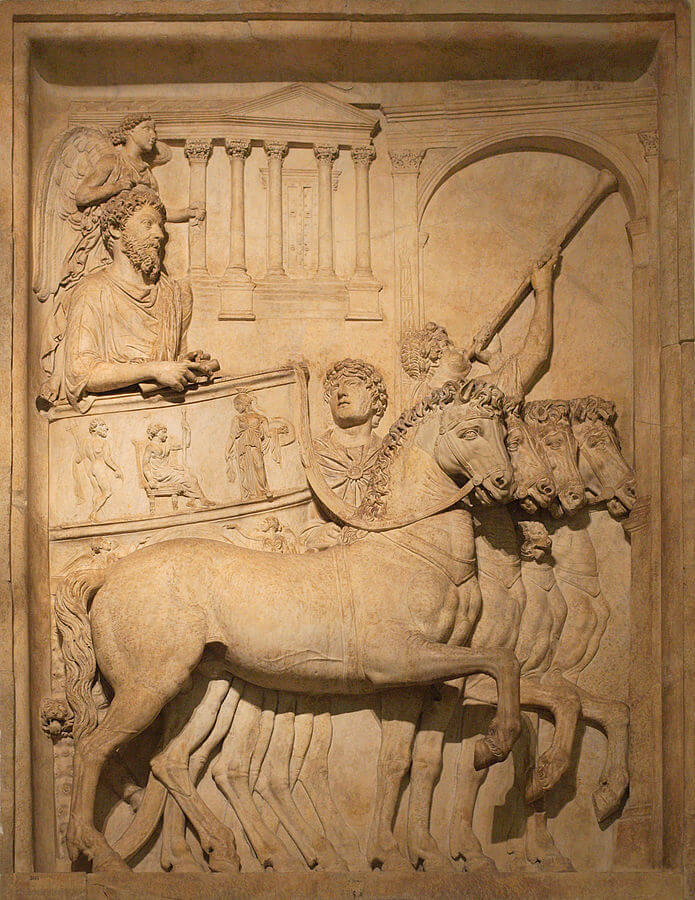

First, let’s try to clarify the origin of the word tarot. Scholars generally agree that ‘tarot’ is the French derivative of the Italian word tarocchi (plural of tarocco). Historians aren’t sure where the term tarocchi or tarocco came from. The first written occurrence of the word tarocchi is found in the ‘Steele Sermon’ published around 1450. It’s possible that tarocco derived from an earlier term: Trionfi, Italian for Triumphs or Roman “royal processions”. Playing cards using four suits in the form of pip cards (an early form of our modern suits: hearts, spades, clubs, and diamonds) did exist prior to tarocchi games. Trionfi most likely referred to the trump cards and helped distinguish it from other styles of card games. Before we look into modern tarot’s birth in Italy, we need to go back to the earliest predecessors of the tarocchi card game. Not in ancient Egypt, or as smuggled treasure from the Knights Templar, but in a less spiritually lofty pursuit: gaming and gambling with playing cards.

Before we look into modern tarot’s birth in Italy, we need to go back to the earliest predecessors of the tarocchi card game. Not in ancient Egypt, or as smuggled treasure from the Knights Templar, but in a less spiritually lofty pursuit: gaming and gambling with playing cards.

Example of Roman triumph art. Bas relief from Arch of Marcus Aurelius triumph. Image source: Matthias Kabel via Wikimedia Commons

The Seeds of Tarot: Early Playing Cards

Like many inventions, the story of playing cards begins in the East. The first playing cards were created in 9th century AD in China during the Tang Dynasty. Paper, the key component to a deck of cards, had been invented long before in 100 BC in China.

Created using woodblock printing, early Chinese playing cards were used in the “leaf” game. In terms of rules and designs, the “leaf” game has more in common with modern-day dominos than playing cards. However, a few centuries later, scholars would begin to see the “leaf” game evolve into cards that use pip systems in four suits.

The Middle East and India: Ganjifa and Malmuk

Chinese printed playing card dated c. 1400. Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

Papermaking technology spread from China to India and then to the Middle East in the 7th century. It wasn’t long after the arrival of paper that India and parts of the Middle East began creating their own variations on playing cards. We know that Chinese playing cards came to India and the Middle East prior to traveling from there to the Western world. While scholars have trouble pinpointing the exact time when playing cards arrived in Persia, now modern-day Iran, the most likely scenario is that cards were one of the many traded goods along the historical Silk Road routes that ran from China to Europe and northern Africa, passing through India and the Middle East along the way.

Ganjifa Card from the mid-18th century. Image source: Ashley Van Haeften on Flickr

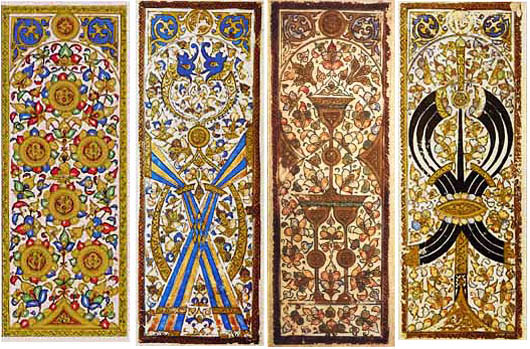

One of the first iterations of playing cards in the Middle East and India were Ganjifa cards. Handpainted Ganjifa cards are still made in India today, and used for astrological divination, although it’s becoming a dying art. A popular variation on Ganjifa, significant for Tarot historians, are the Mamluk playing cards. Tarot enthusiasts will recognize the designs of the pips. The ornate flourishes of the pips and the bending of the swords mirror subsequent European designs still used today. It’s in the Mamluk playing cards that we find the modern precursors of pips familiar to European tarot decks: coins, polo-sticks (later to become wands or staves), swords and cups.

Four Mamluk Playing Cards c. 1500. Image source: Wikimedia Commons via Countakeshi

The Flemish Hunting Deck

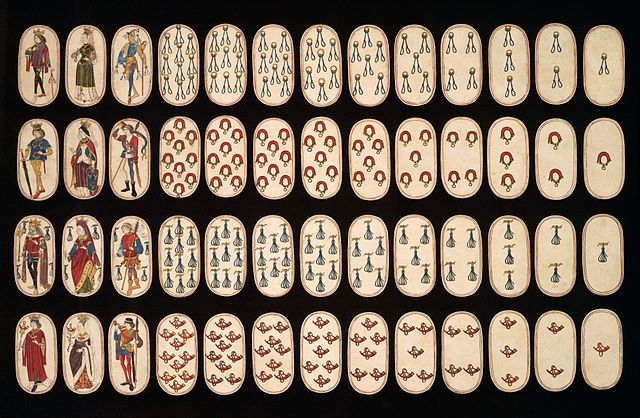

Flemish Hunting Deck Oldest Known Playing Cards. Image source: Wikimedia Commons

It’s worth discussing a development in playing card history that in some ways could be an early predecessor of tarot. The Flemish Hunting Deck is one of the oldest surviving intact playing card decks. Printed playing cards already existed prior to this, but the presence of pictorial court cards is thought to be a new development in playing cards that did not depict only numbered suits, but also as figures with hierarchical status within the game. These are the basis for our modern court cards: Knights, Queens, and Kings.

The famous Flemish Hunting Deck was initially misidentified as a 16th-century tarot deck due to their well-preserved nature. They were originally sold to a Dutch antiques dealer in 1978, who suspected they might be older, for 8,000 NLG (around $4,000 USD at the time). Later, after being verified as the oldest playing card set in the existence, they were sold at auction in 1983 at Sotheby’s in London for $143,000 to the Metropolitan Museum of Art ($351,692 USD in 2017).

The Tarot Arrives: Visconti family

Filippo Maria Visconti: Duke of Milan (1412-1447), patron of the arts, and primary commissioner of the Visconti-Sforza Tarot. Image source: Wikimedia Commons

Francesco Sforza: Filippo Visconti’s son-in-law, Duke of Milan (1450-1466) and co-commissioner of the Visconti-Sforza Tarot. Image source: Wikimedia Commons

Bianca Maria Visconti: Duchess of Milan (1450-1468), Filippo’s daughter, Francesco’s wife, and possible inspiration of some of the female figures in the Visconti-Sforza Tarot. Image source: Wikimedia Commons

Around the mid-15th century, Filippo Maria Visconti, the Duke of Milan, along with his son-in-law, Francesco Sforza, commissioned a painted, gilded set of tarocchi cards. The copy that resides in the Piermont-Morgan library is thought to have been made around 1451. The Visconti-Sfzora tarot was commissioned around the same year as the sermon denouncing the game. The deck gives us a glimpse of tarot as we know it today: a set of cards consisting of pictorial trumps and four sets of pip cards. Pip cards are the equivalent of our modern-day suits. In the Western world, the most common suit system are hearts, clubs, diamonds, spades. At the time of tarot’s creation in Italy, it was cups, staves, coins and swords.

The individual cards of the first pack of the Visconti-Sforza tarot are rare. Only fifteen variations of this hand painted and gilded deck are known to exist. The Morgan Library’s collection of thirty-five cards is the largest set housed in one location. The second largest collection, at twenty-six cards, is across the sea in the Accademia Carrara di Belle Arti di Bergamo, a Fine Arts Academy in Bergamo, Italy. The remaining cards known to exist, a set of thirteen, are in the private art collection of the Colleoni family in Bergamo, Italy. Interestingly, the Colleoni family were an influential ruling family in Milan, but were ousted from power in the early 1400s by the Visconti family.

If we assume that the Visconti-Sforza deck contains the number of trumps and pips that typical tarocchi cards in the 1400s and early 1500s used, it would contain 78 cards. If you do the math, you’ll notice that this deck is only 74 cards. Where are the missing cards?

The Devil, The Tower, The Three of Swords, and the Knight of Coins are missing and, due to the ephemeral nature of paper, probably lost to time. The majority of Visconti-Sfzora reproduction decks include speculative recreations of the missing cards. There’s a variation of this deck in the Cary Collection of Playing Cards at the Yale University Library that may have been produced ten years before the Piermont-Morgan one. The Cary-Yale deck contains interesting variations on the trumps and court cards. In the Cary-Yale decks, trumps contain the biblical “three theological virtues”: faith, hope and charity. The concept of the three theological virtues can be found in another type of Italian playing card that existed in Italy at the same time: the Minchiate deck. Minchiate used a playing style similar to tarocchi.

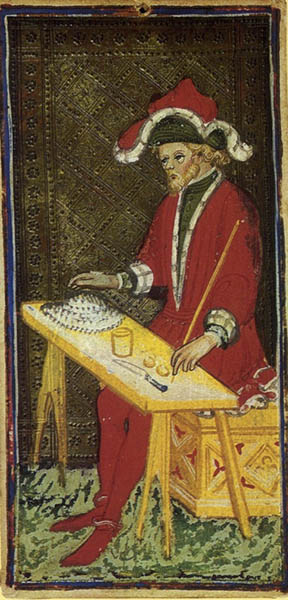

The Juggler (Bagatto) from the Piermont Morgan Visconti-Sforza Tarot. Image source: Cesar Ojeda via Flickr Creative Commons

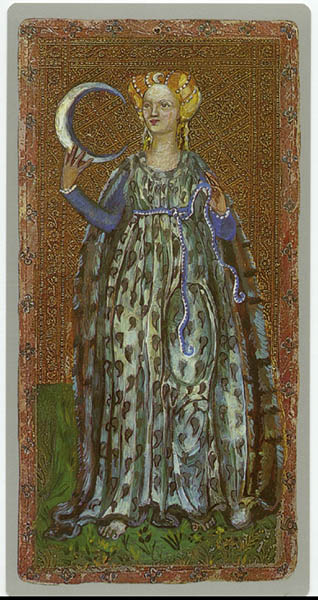

The Moon from the Visconti-Sforza Tarot Bembo Bonifacio Collection. Image source: Cesar Ojeda via Flickr Creative Commons

The Popess from the Piermont Morgan Visconti-Sforza Tarot. Image source: Cesar Ojeda via Flickr Creative Commons

The Popess from the Piermont Morgan Visconti-Sforza Tarot. Image Source: Image source: Piermont Morgan Library

The Popess from the Cary-Yale Visconti Tarot. Image source: Cesar Ojeda via Flickr Creative Commons

Sola Busca and Lost Tarot in the 15th century

Il Matto Sola Busca Tarot. Image source: Taropedia

Palas Sola Busca Tarot. Image source: Wikimedia Commons

Sola Busca Tarot Seven of Discs. Image source: Taropedia

The oldest complete tarot deck is the Sola Busca. It was printed in 1491, around 40-50 years after the Visconti-Sforza tarot. The Sola Busca tarot was created using copper etchings, giving it finer detail and shading than the more common woodblock-printed tarocchi decks of the time. The original printings were black ink on white paper, and then shipped out to other studios in Italy for painting and gilding. The end result was a card with an appearance similar to the gold foiling on Visconti-Forza tarot decks. It’s worth noting the similarities between some of the Sola Busca’s pips and the subsequent minor arcana in modern Rider-Waite-Smith tarot decks (we’ll get to that ubiquitous deck later). Pamela Coleman Smith, artist of the Rider-Waite-Smith deck, would have been able to view the Sola Busca deck at the British Museum in 1909.

Ten of Swords from the Sola Busca Tarot. Image source: Wikimedia Commons

Ten of Wands from the Waite Smith Tarot. Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

Ten of Swords from the Waite-Smith Tarot. Image source: Wikimedia Commons

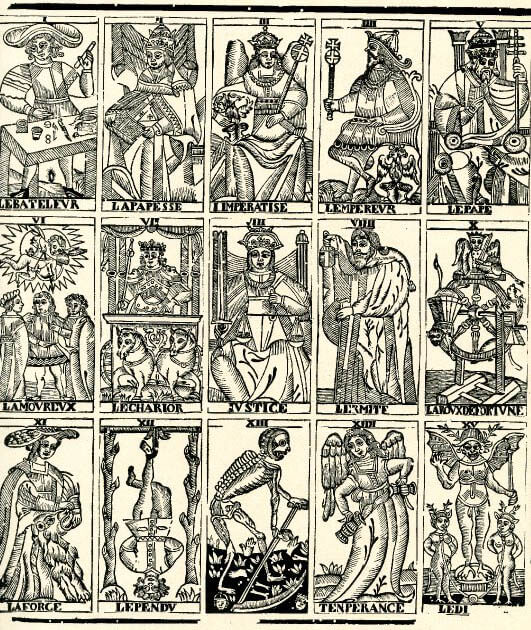

During the late 15th century, a glut of tarot decks were being created via woodblock printing for mass consumption. While no whole decks of the cheaper copies of tarocchi packs remain, there are uncut sheets of cards that were either flawed or left over from the printmaking process. We’ll see the aesthetic design of early Italian woodblock printed decks carry over into the later designs of the French Marseille decks.

From the late 1600s to early 1700s tarot exploded in popularity, with decks being produced across Europe, particularly in France, Switzerland, Germany, and Belgium. As the late 1700s approached, a rebellion was brewing in France. Not just civil revolt, but the seeds of a mystical revolution.

German Tarot Cards – Italian Style – 1750. Image source: British Museum

The French Occult Revolution

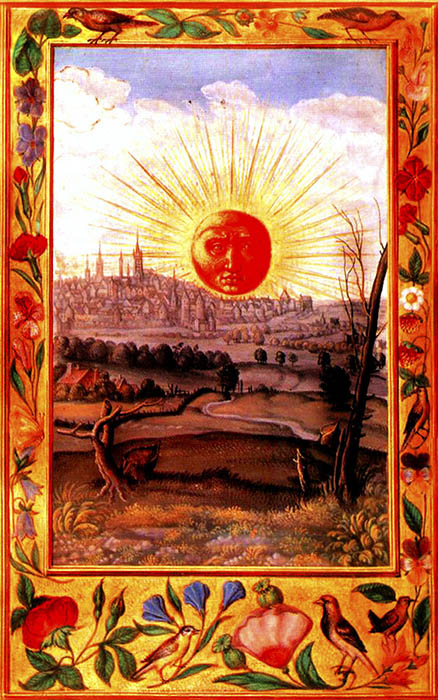

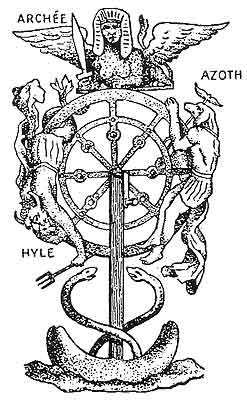

Splendor Solis – 16th-century Alchemical text. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

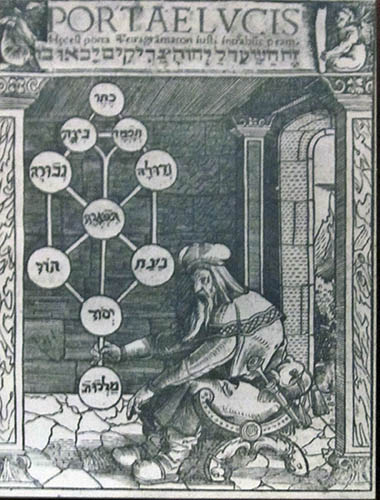

Art from Portae Lucis – Gates of Light: a treatise on Kabbalah. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

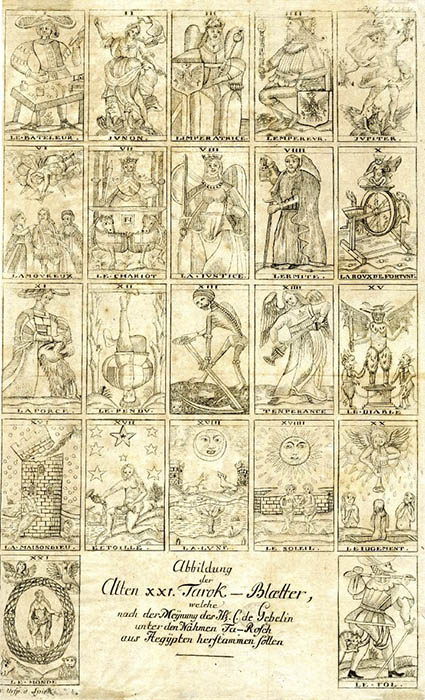

A sheet illustrating 21 tarot cards with DeGebelin meanings. Image source: British Museum Collection.

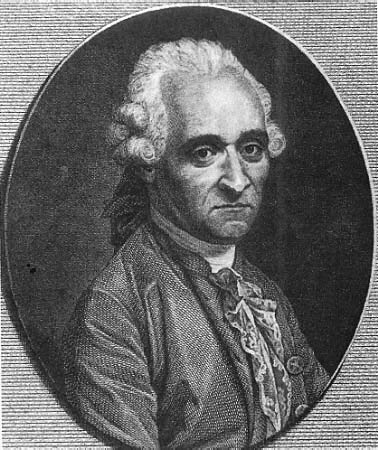

Antoine Court DeGebelin. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

In the midst of chaos during the French revolution, another hidden revolution was taking place.

Before we begin talking about the mystical orders associated with tarot, I think it would be beneficial to define the term ‘occult’. The word occult derives from the Latin “occultus” meaning hidden or secret. Many have negative associations with the term occult. Keep in mind, this refers to anything under the umbrella of esoteric and arcane knowledge (alchemy, metaphysics, astrology: almost anything that can’t be measured empirically). In the mid-1700’s, we encounter huge shifts in philosophical thought in the Western world. One of those shifts is a sub-movement of individuals gathering together to examine hidden knowledge and mysteries in ecclesiastical and ancient magical texts. This is a time where theories of alchemy intermingle with scientific discoveries. Both are a quest to unravel how the universe works. It’s during this period we see philosophers and occultists being informed by branches of Eastern and Abrahamic mysticism.

One of the first to publish writings on a mystical usage for tarot was Antoine Court de Gébelin. De Gébelin was a writer, pastor and Freemason. In 1781, he wrote a treatise proclaiming that tarot was based on the ancient Book of Thoth (allegedly a tome of Egyptian knowledge written by the god Thoth). He’s credited as one of the primary sources of the myth of tarot’s ancient Egyptian origin. It’s a myth that’s stuck and still persists to this day. He suggested that Egyptian priests had encoded the contents of the book into tarot via its symbols. He also suggested magical correspondences to each card using Hebrew letters. Later, those ideas would be expanded on by the influential ceremonial magician Eliphas Levi.

The idea of tarot correspondences suggests that particular cards have other metaphysical meanings. We see this today in the form of tarot suits representing metaphysical elements (eg. Cups as water, Swords as air, Wands as fire and Pentacles as earth). De Gébelin also discussed connections between tarot and Jewish mysticism in the form of Kabbalah.

The Dawn of Modern Tarot

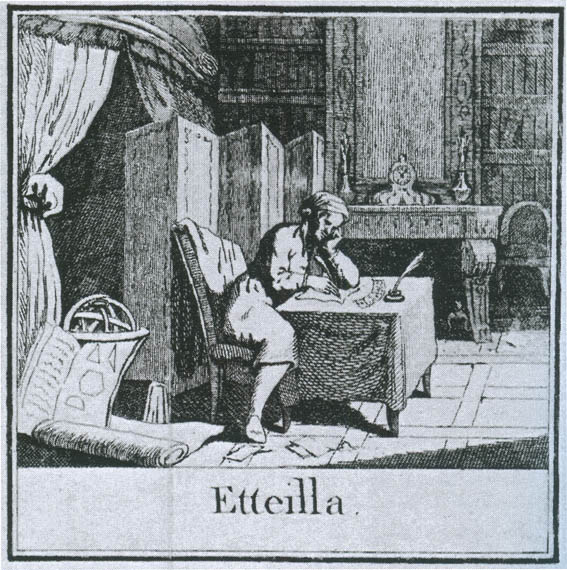

Jean-Baptiste Alliette (Etteilla). Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

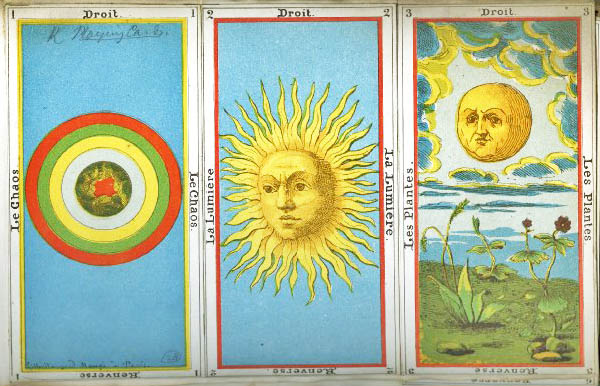

Etteilla Tarot. Image source: British Museum

In 1770, French occultist Jean-Baptiste Alliette, who published under the name Etteilla, wrote what is considered the first texts on how to use tarot as a system of divination: “Etteilla, A Way to Entertain Yourself With a Deck of Cards”. Twenty years later, in 1790, he would write another text about tarot and the Egyptian Book of Thoth. Etteilla’s work expanded on Antoine Court de Gébelin’s essay. Etteilla elaborated further on correspondences and astrological connections within the images of tarot cards. He would further popularize the idea of tarot’s ancient Egyptian origins. Etteilla went on to develop his own tarot deck incorporating the concepts of the four elements along with expanded magical and astrological correspondences.

Eliphas Levi was a French ceremonial magician and prolific author. Levi wrote one of the most influential volumes on the Western Mystical tradition entitled “Dogme et Rituel de la Haute Magie (English title: “ Dogma and Ritual of High Magic”). Levi elaborated on Etteilla and De Gébelin’s tarot and Hermetic Qabalah connections. His text served as potent inspiration for many newly forming mystical orders in Europe. Through a future translator of his work, Levi would play a small role in the creation of the most influential, enduring tarot decks of the modern world.

Eliphas Levi’s Wheel of Fortune design. Image source: Aeclectic Tarot

A Glimpse Before the Waite-Smith Tarot: 19th and early 19th Century Tarot in Images

Late 19th-century Venetian Tarot Cards. Image source: The British Museum

Il Diavolo reproduction of the Soprafino-Gumppenberg Tarot (1840). Image Source: Sigo Paolini via Flickr Creative Commons

Il Papa The Pope reproduction of the Soprafino-Gumppenberg Tarot (1840). Image Source: Sigo Paolini via Flickr Creative Commons

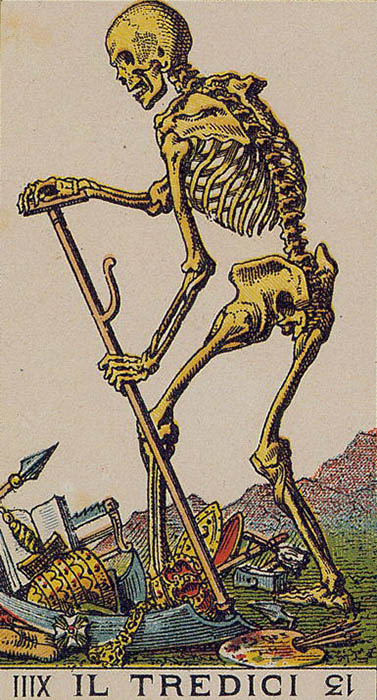

Il Tredici Death reproduction of the Soprafino-Gumppenberg Tarot (1840). Image Source: Sigo Paolini via Flickr Creative Commons

Le Stelle The Star reproduction of the Soprafino-Gumppenberg Tarot (1840). Image Source: Sigo Paolini via Flickr Creative Commons

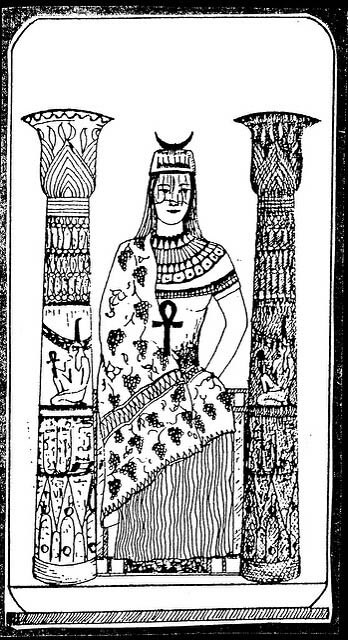

The High Priestess from the “Egyptian” Tarot (1901). Image source: n0cturbulous via Flickr Creative Commons

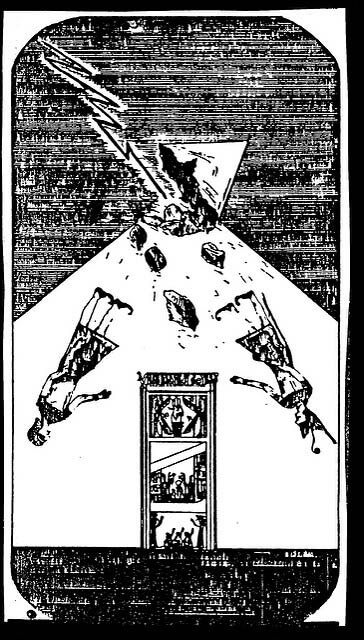

The Tower from the “Egyptian” Tarot Tarot (1901). Image source: n0cturbulous via Flickr Creative Commons

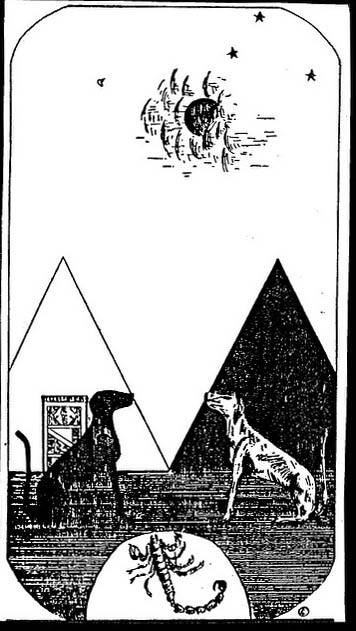

The Moon from the “Egyptian” Tarot (1901). Image source: n0cturbulous via Flickr Creative Commons

The Waite-Smith Tarot Deck

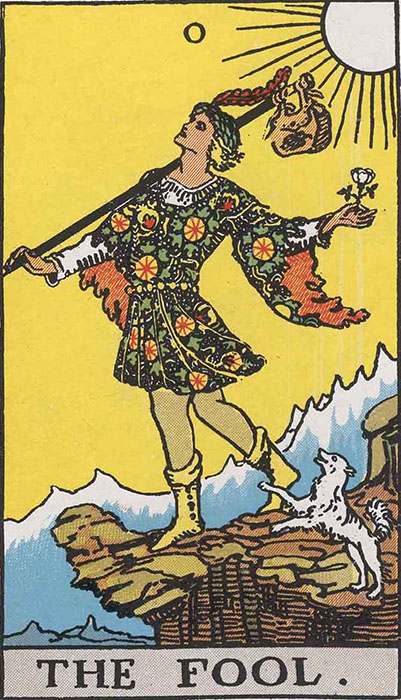

The Fool Tarot Card Rider Waite Smith. Image source: Wikimedia Commons

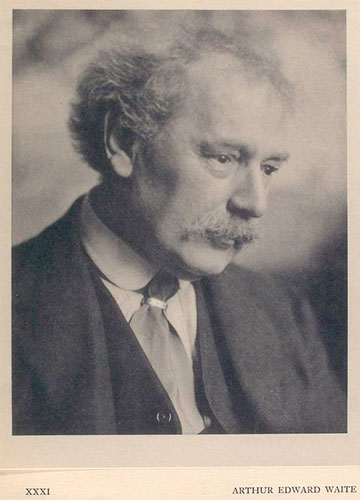

Arthur Edward Waite. Image source: Wikimedia Commons

Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers: a founding member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. Image source: Wikimedia Commons

It was from a personal loss that university clerk and poet Arthur Edward Waite would begin his journey into mysticism. His sister, Frederika, had passed away in 1874 when he was 17 years old. Scholars believe her death led Arthur to research magic and mysticism. Waite discovered Eliphas Levi’s writing in the Library of the British Museum in 1881. He would become one of the primary translators of Levi’s works from French into English. A few years later, the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn was formed in 1887 by William Wynn Westcott, Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers, and William Robert Woodman. Golden Dawn was a magical order dedicated to spiritual growth and enlightenment through ritual. It was a short-lived organization, disbanding by 1903. Regardless, the Golden Dawn left a profoundly influential mark on English metaphysical studies that is still felt today. Arthur Waite floated in and out of the organization until its disbanding in 1903.

During its short existence, a number of writers, actors and artists participated in the Golden Dawn’s rituals. Some of the members of the Golden Dawn’s rosters included poet W. B. Yeats, actress Ellen Terry, author Bram Stoker, and author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. During Waite’s time in the Golden Dawn, he met a young illustrator and stage crafter through W. B Yeats: Pamela Coleman Smith.

Pamela Colman Smith: artist of the Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot Deck. Image source: Wikimedia Commons

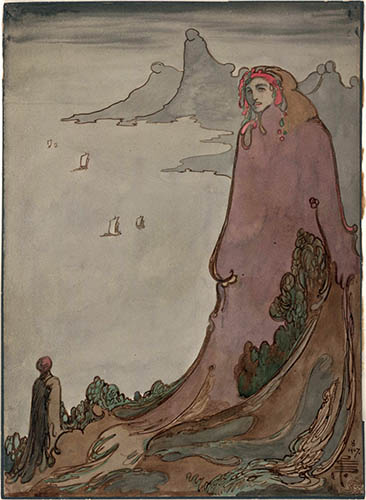

Pamela Coleman Smith’s Artwork for Beethoven’s Sonata No. 11.

Pamela Coleman Smith was born in London to American parents. Shortly after, she moved to Jamaica with her family. Smith grew up traveling between Kingston, London, and Brooklyn. She was one of the first waves of art students at the now prestigious Pratt Institute in New York. Pamela moved back to London after the death of her mother and father. There she became involved with the Lyceum Theatre group where she met Bram Stoker and actress Ellen Terry (owner of the troupe, famous actress at the time, and possible inspiration for the image of the Queen of Swords). Pamela traveled with the theater company while assisting with costuming and set design. When she returned to London, she was able to rent a studio where she hosted open houses and storytelling.

In 1901 W. B. Yeats introduced her to the Order of the Golden Dawn where she met Arthur Waite. Years after the disbanding of the organization, Arthur Waite would approach Pamela to create a tarot deck that would appeal to the modern art world. Waite knew Pamela was a talented artist, having worked professionally as an illustrator and became the first painter to be shown at Alfred Stieglitz’s gallery in New York. At 31 years old, she already had a successful book and a self-published magazine under her belt. Waite was interested in creating a modern tarot deck. He was more concerned with tarot as a tool for personal and spiritual transformation than a way to divine the future. Waite’s emphasis would be on the symbolic meaning of the imagery and how it could be used as a catalyst for spiritual transformation.

Waite gave the job of illustrating his tarot deck to Smith. Later, in a letter to photographer Alfred Stieglitz, Smith wrote that she received “a big job for very little cash” for 80 paintings to be made into a tarot deck. The Waite-Smith tarot deck was published in 1910 by Rider and Son’s Imprints in London. Although her tarot deck would become hugely popular in the United States during the 1960s and 70s, the deck was also a hit at the time it was published. In fact, it was so popular that it was bootlegged just a few years later. However, either due to her commission contract (or lack thereof), she wasn’t party to any copyright or financial gains during her lifetime. In 1951 Pamela passed away without having seen any financial returns for the creation of one of the most popular tarot decks in history. At the time of her passing, her home and its contents were sold in order to recover debt.

Before closing this chapter on the birth the of Rider-Waite-Smith tarot, the nomenclature of the deck (and the implication of) should be discussed. For many decades, the deck has been known as the Rider-Waite tarot. “Rider” refers to the publishing house where it was printed. Waite is, of course, the driving force behind the initial idea of the deck’s creation, the primary symbolism of the trump cards, and the meanings associated with the deck via The Pictorial Key to the Tarot. The artist and fellow Golden Dawn member, Pamela Coleman Smith, who created the now iconic images has not historically been included in the popular name of the deck. Robert M. Place details a compelling analysis of the extent of Smith’s contributions in his book The Tarot: History, Symbolism, and Divination (see Resources and Additional Reading). Smith took six months to complete a set of 80 paintings for the deck. Six months is an extremely short period of time for a commission of that scale. Although Smith certainly had guidance from Waite on the symbols to use in the Major Arcana. Smith was given much more room for her own interpretation of the Minor Arcana.

As she was a Golden Dawn member, Pamela Smith was already familiar with many of the core symbols of the tarot. It’s important that Pamela Coleman Smith receive the credit she deserves in the co-creation of this iconic deck. Hence, the new naming of the deck as the Waite-Smith or Rider-Waite-Smith tarot.

Modern tarot

Left to right: Pearl Brooksmith, Aleister Crowley, and Lady Frieda Harris. Image source: Taropedia

Thoth Tarot by Image Source: Kyknoord via Flickr Creative Commons

In 1940, the infamous occultist, and former member of the Golden Dawn, Aleister Crowley along with artist, Lady Freida Harris, developed the Thoth tarot. Like A. E. Waite, Crowley wanted a tarot deck that incorporated his own studies and understanding of mystical systems. Like other occultists in the past who’ve tried their hand at developing a new iteration of tarot, Crowley’s Thoth has new correspondences for astrological properties and the Kabalah. The Thoth tarot initially did not enjoy as much popularity as the Waite-Smith tarot, possibly due to a lack of printed copies in circulation at the time of its completion. Still, today it’s a well-known modern variation that has inspired other popular decks such as the Mary-El by Marie White and the Tabula Mundi Tarot by M.M. Meleen.

The Order of the Golden Dawn may have been a relatively short-lived organization, but a few splinter groups formed from it. It helped that Israel Regardie, a member of the Golden Dawn and Aleister Crowley’s personal secretary, published most of their rituals and correspondence materials. One splinter group still exists today: The Builders of the Adytum, or B.O.T.A.. The organization was started as a way to share and democratize esoteric teachings on tarot via the Golden Dawn philosophy. B.O.T.A. still offers classes by mail on tarot and Qabalah.

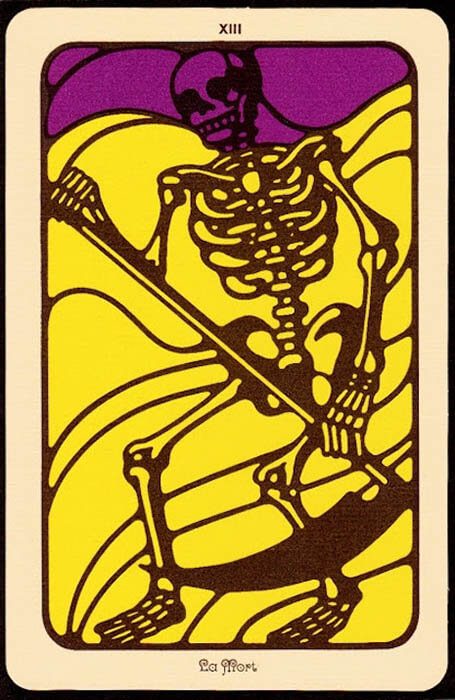

Lineweave Tarot La Mort Death card. Image source: Dangerous Minds

Aquarian Tarot Temperance Card by Palladini David published by U.S. Game Systems

The 1960s marked a trend toward more personalized, intuitive approaches to tarot reading. Esoteric correspondences were still popular, but in 1960, Eden Gary published “The Tarot Revealed”, intended as a straight forward method of reading the cards for divination. Gary may have been the first to apply a narrative to the progression of the trumps in the Major Arcana by describing the Fool’s Journey. The Fool’s Journey relates the tarot trumps to Jungian archetypes and parallels Joseph Campbell’s idea of the Hero’s Journey. Carl Jung never wrote in detail about his ideas of how archetypes relate to tarot (he does mention it in letters and seminars). But tarot fits in neatly with the concept of viewing spiritual journeys as archetypically mirrored in stories or motifs. The same can be said for Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey being applied to tarot as the “Fool’s Journey”. This idea suggests that the order of the Major Arcana follows a narrative of the Fool moving through a quest where he meets, or metaphorically becomes, the other characters of the Major Arcana cards. Along with other changes in spiritual and social movements in the West, Tarot went through a renaissance during the New Age movement in the 1970s. Later, authors such as Mary K. Greer would publish works emphasizing history, symbolism and the individual’s own intuition in conjunction with the tarot.

Here we are: Tarot and the Post-Modern Era

What is tarot now? Tarot seems to be having another moment in history. It’s being used as a divination tool, an idea generator for writers, a spiritual teacher, a vehicle for parody, and a therapist-in-a-box. Tarot exists in a time where it’s understood that methods of reading the cards can be approached in a purely intuitive manner: just read what you see on the cards. It can also be approached with nuanced understandings of elemental dignities and advanced systems of correspondences. There will always be individuals on both sides insisting on a single, correct approach to tarot (history repeats itself), but most modern-day thought leaders on tarot are quick to point out there’s room for a variety of approaches.

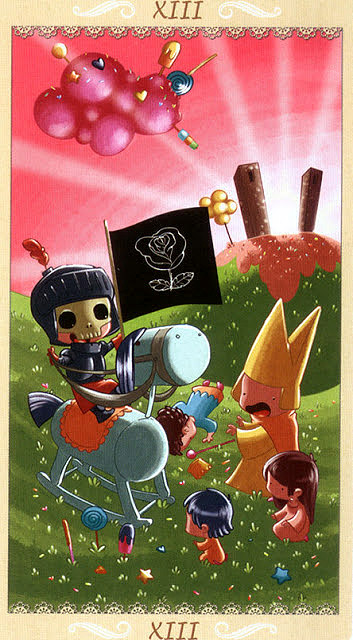

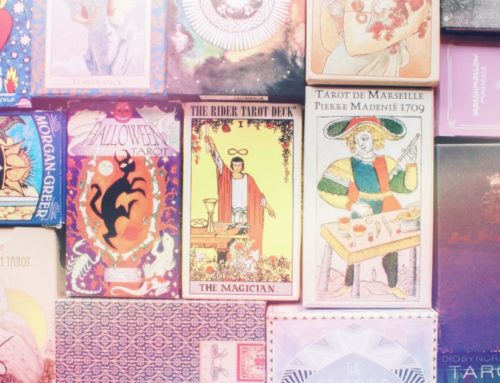

The relative ease of having a tarot deck printed has created a renaissance of indie tarot decks and reprints of historical tarot packs. There’s a strong movement in the tarot community for the creation of decks that incorporate diversity in their imagery, as well as challenge the more traditional gender roles within the deck.

Nine of Swords Sasuraibito Tarot

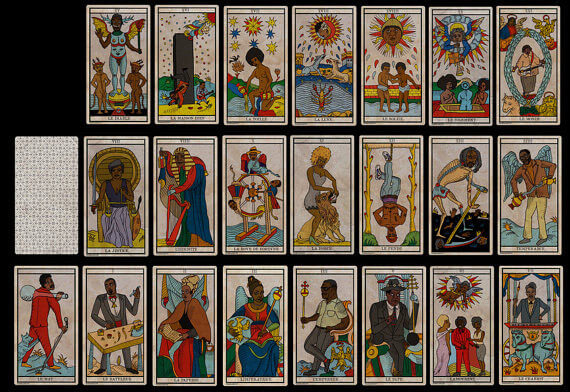

Black Power Tarot by King Khan and Michael Eaton.

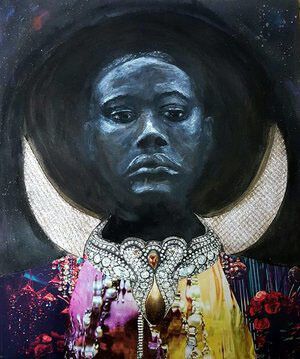

Moon from Dust Onyx II Tarot

Where will tarot go from here?

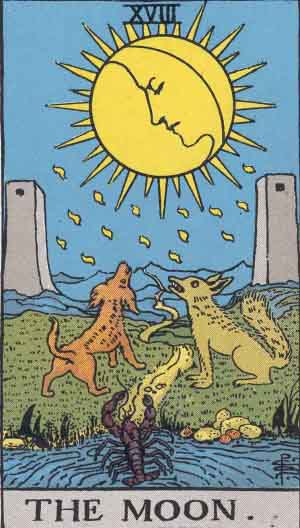

The Moon Tarot Card Rider Waite Smith. Image source: Wikimedia Commons

Resources and Additional Reading

General Tarot History

The Encyclopedia Of Tarot, Vol. 1 by Jean Huets and Stuart R. Kaplan [Books] [affliate link]

The Tarot: History, Symbolism, and Divination by Robert Place [Books] [affliate link]

A Wicked Pack of Cards: Origins of the Occult Tarot by Michael Dummett [Books] [affliate link]

The Etymology of Tarot from Spiral Nature

Tarot History from Tarot Heritage

Early Playing Cards

The Chinese “Leaf” Game by David Parlett from

Mysore Ganjifa: Reviving a Forgotten Art Form by Aishwarya Suresh from The Better India

Mamluk Playing Cards from World of Playing Cards

Visconti Family from the Encyclopædia Britannica

Visconti-Sforza

Tarot History – The Cary-Yale Visconti Tarot Deck [Images] from Tarot History

The Visconti-Sforza Tarot Card [Images] from the Morgan Library and Museum

Cary-Yale Visconti-Sforza [Images] from the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

The Visconti-Sforza Tarot from World of Playing Cards

Sola Busca and Lost Tarot in the 15th Century

Sola-Busca Tarocchi from World of Playing Cards

Minchiate Cards for Divination: My Review from Benebell Wen

Italian Tarot in the 15th Century from Tarot Heritage

The French Occult Revolution

From Alchemy to Chemistry from Khan Academy

History of Alchemy from Ancient Egypt to Modern Times from Alchemy Lab

Hermetic Qabalah from Wikipedia

Eliphas Levi from Wikipedia

The Dawn of Modern Tarot

A History of Seeing the Future: Tarot Cards in Early Modern Europe by Michael Lynn from The Ultimate History Project

Grand Etteilla’s Secret from Camelia Elias

Grand Etteilla Tarot Cards [Images] from Queen of Tarot

The Soprafino Deck of Carlo Dellarocca from Tarot Heritage

A History of Egyptian Tarot Decks from Meta Religion

The Tarot of the Bohemians By Papus (Gérard Encauss) from Sacred Texts

The Waite-Smith Tarot Deck

The Unsung Woman Artist Behind Your Tarot Cards from Hyperallergic

The Pictorial Key to the Tarot By Arthur Edward Waite from Sacred Texts

A. E. Waite and the Occult from The Oddest Inkling

Where Did the Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot Originate? by Jean Bakula from Exemplore

The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, 1888-1901 from the Branch Collection

Victorian Egyptomania: How a 19th Century Fetish for Pharaohs turned Seriously Spooky by Nell Darby and James Hoare from History Answers

Modern tarot

Frieda Lady Harris by Richard Kaczynski from The Hermetic Library

The Art of Frieda Harris from John Coulthart

Women & The Occult – Lady Frieda Harris: Artist of the Thoth Tarot from Red Wheel/Weiser

Aleister Crowley from OTO Grand Lodge

Aleister Crowley: Man, Beast, Human, Genius by Mo Abdelbaki from Gaia.com

B.O.T.A. Builders of the Adytum

Eden Gray’s Fool’s Journey by Mary K. Greer

The Hero’s Journey from The Writer’s Journey

Carl Jung and Jungian Archetypes in the Tarot: The Various Aspects of Our Selves from Labyrinthos Academy

Here we are: Tarot and the Post-Modern Era

It’s in the Cards: Exploring the Indie Tarot Renaissance by Haley Houseman from Sanctuary

Tarot of the QTPOC from Asali Earthworks

#TarotsoWhite: A Conversation about Diversity in Our Cards from Little Red Tarot

Gender Bending the Tarot by Theresa Reed

Excellent information and lots of detail. I love all the reference pics that correspond to the history aspect of Tarot.

Thank you Suzie! I tried my best to dig up images of the significant decks… plus their creators!

Thank you so much. I just wanted to thank you for your dedication to information about the evolution of the tarot. Your gift helps inform the reader to consider the the history as well as the symbols. For me to include the wisdom of what has gone before to present day. That symbiotic depiction speaks a thousandfold truths no matter what age we live in. Thank you again for your wonderful work. Linda